Sea Star Wasting Disease Culprit Identified!

Researchers have identified the causative agent behind this outbreak, a strain of the Vibrio pectinicida bacteria. While further research is still needed to understand key aspects of the outbreak, this breakthrough will help strengthen sunflower star recovery efforts.

In 2013-14, one of the largest marine disease outbreaks on record, Sea Star Wasting Disease (SSWD), swept through sea star populations in the eastern Pacific. Before the SSWD outbreak, over 6 billion sunflower stars roamed the nearshore marine ecosystems from Alaska down to Baja California. The outbreak caused over 5 billion of those stars to turn into goo, killing over 90% of sunflower stars across their historic range and rendering the species functionally extinct in California and Oregon.

Because sunflower stars are a keystone species, maintaining ecosystem balance by scaring and eating kelp-grazing purple urchins, their disappearance had cascading impacts across the Pacific Coast. Purple urchin populations proliferated, mowing down kelp forests and heavily contributing to the loss of over 97% of Northern California’s kelp forests in the last decade alone.

Now, researchers from Friday Harbor Labs, the University of British Columbia, Hakai Institute, and other partners have identified the causative agent behind this outbreak, a strain of the Vibrio pectinicida bacteria. While further research is still needed to understand key aspects of the outbreak, this breakthrough will help strengthen sunflower star recovery efforts by allowing partners to better understand disease risk with animals under human care and ensuring effective quarantine protocols when moving animals between places, track pathogen abundance in the wild, and factor into restoration planning.

The four-year international research effort was led by scientists from the Hakai Institute, the University of British Columbia (UBC), and the University of Washington—and was conducted in collaboration with The Nature Conservancy, the Tula Foundation, the US Geological Survey’s Western Fisheries Research Center, and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

As detailed by the Tula Foundation, the team of scientists explored many possible pathogens, including viruses, first looking in sea star tissues before homing in on the high levels of V. pectenicida in sea star coelomic fluid. Researchers then created pure cultures of V. pectenicida from the coelomic fluid of sick sea stars. Researchers injected the cultured pathogen into healthy sea stars, and the ensuing rapid mortality was final proof that V. pectenicida strain FHCF-3 causes SSWD. After a lengthy review process, the results were published in August of 2025 in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, engendering significant media coverage and public awareness about the pathogen discovery and the plight of sunflower stars at large.

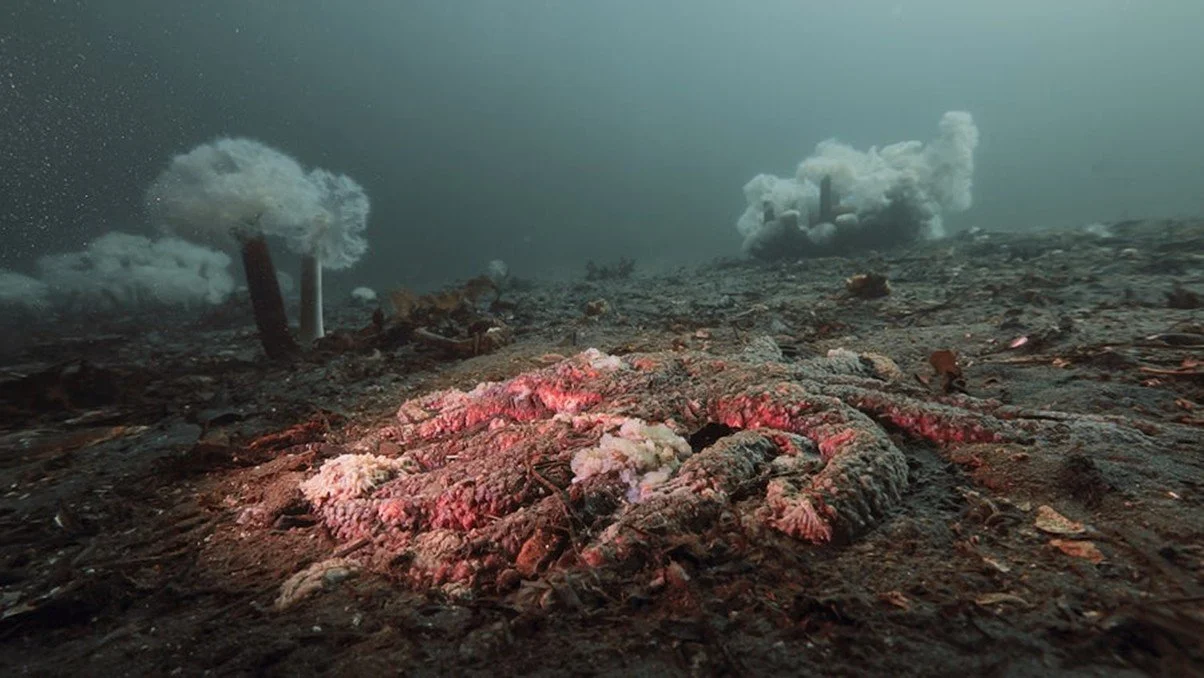

A sunflower sea star is reduced to goo on British Columbia’s Calvert Island in 2015. SSWD has killed billions of sea stars—representing over 20 different species from Alaska to Mexico—since 2013. Grant Callegari/Hakai Institute

While the initial outbreak of SSWD in 2013 appeared before an ensuing marine heatwave, human-caused climate change likely exacerbated the disease's spread. Widespread symptoms of wasting have historically occurred periodically in sunflower star populations, but the 2013-14 vibrio-caused outbreak is unprecedented in scope and mortality. Signs of the SSWD outbreak first appeared in 2013, before a marine heatwave known as ‘The Blob’ began in the Eastern Pacific in 2014. However, this multi-year period of abnormally warm ocean temperatures likely greatly exacerbated the spread of SSWD, allowing this outbreak to become more widespread and destructive than previous sunflower star wasting events.

Climate modeling studies have found that ‘The Blob’ was up to 50% more likely to have occurred due to human-caused climate change, which increases the frequency and scale of extreme weather events. Further research is needed to determine the exact relationship between warming temperatures and SSWD spread, but other strains of Vibrio bacteria have been known to proliferate and cause disease in warm water events

The ability to test for the Vibrio pathogen at conservation facilities will allow a better understanding of disease risk for sunflower stars under human care. By knowing whether or not an existing or potential future sunflower star aquaculture facility has the vibrio pathogen within its systems, we can make better informed decisions about population management among partner institutions. Testing ability will also provide higher confidence in quarantining systems, as testing can confirm the absence of the pathogen. Similarly, the ability to test for the Vibrio Pathogen in the wild can potentially significantly enhance the efficacy of restoration efforts. Testing the relative abundance of the pathogen in different open ocean environments can inform decision making regarding reintroduction efforts, and enable research into optimal locations and times to focus restoration efforts.